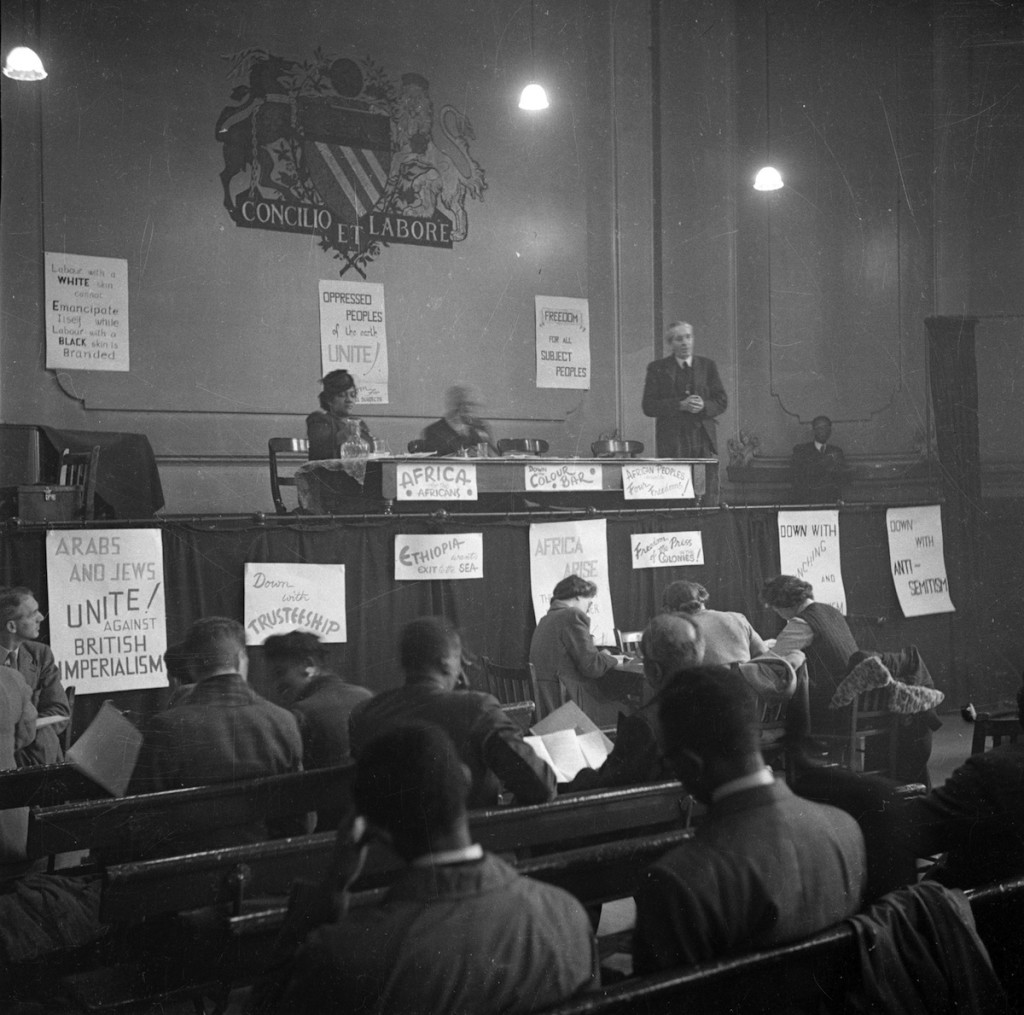

On a warm summer day in July 1900, a group of people of African descent gathered from all over the world for a conference in Westminster Town Hall, London. The aim of the conference, according to the primary conveners, was to “influence public opinion on existing proceedings and conditions affecting the welfare of blacks in various parts of the world.” The conference lasted for two days (from the 23rd to the 25th), and due to its strategic timing on the cusp of the twentieth century, it was hailed by some black revolutionary thinkers of the time as, “a precursor to the 20th century” — a sign of the important work to be done by, and for the black race in the new century.

In a paper that was presented at the conference, a young black Professor, William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (W.E.B. Du Bois) noted that “In the metropolis of the modern world, in this the closing year of the nineteenth century, there has been assembled a congress of men and women of African blood, to deliberate solemnly the present situation and outlook of the darker races of mankind.” Du Bois would go on to become one of the biggest proponents of the movement formed from the gathering. The conference in question was called the Pan African conference, and it signalled the public, organized birth of the Pan African movement, or Pan Africanism. But the idea in itself had been in the works for at least, half a century.

The Precursor to Pan Africanism

Two major events precipitated the rise in Pan African thinking. First, was the British abolition of slavery in Africa, which gave rise to increased British colonial influence in Africa, and the growth of a cosmopolitan, colonial settlement in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Second, was the furore around the abolition of slavery in the United States of America, which inadvertently gave rise to the “emigrationist” movement, which in turn, led to the resettlement of thousands of African Americans in Liberia, and a consequent cultural, economic and social intercourse between African Americans and Africa.

Event 1: Abolition of Slavery in Africa.

When the British abolished slavery in Africa in 1833, the popular reasoning in London was that passing the anti-slavery law was all that was necessary to kill the ignoble trade. However, the continuous, large-scale trade in slaves on the West African coast decades later, showed that the extent and popularity of the trade among Africans had been grossly underestimated and that the law had to be enforced militarily. This led to the introduction of the British Anti-Slavery Squadron to the coast of West Africa. The squadron patrolled the routes of the slave ships, intercepting many of them in the process. The rescued slaves were eventually resettled in Freetown, Sierra Leone — a colonial settlement in West Africa at the time.

Due to the advantage of western education, and perhaps, close proximity to direct British colonial and cultural influence that living in Freetown granted the rescued slaves and their children, some of the most influential Africans in the nineteenth century, and earliest Pan African advocates took their roots in this sphere. Some important names to note are Samuel Ajayi Crowther, Orishatukeh Faduma, John Otunba Payne, and Mojola Agbebi. This particular event — the abolition of slavery in Africa — and the characters that spawned off it formed one of the two pillars of Pan Africanism.

Event 2: Abolition of Slavery in America

Slavery was officially abolished in the United States in 1864 after the American Civil War, but abolition took place in some states in the union before then. For some time pre and post abolition, there was some measure of tense relations among the would-be equal races. In the white community, there were two schools of thought; one that advocated for the immediate recognition of the full rights of former slaves, and their subsequent conscription into civil society; and the other, which considered blacks as inherently mentally, culturally and socially inferior to whites, and hence, could not be drafted into society as equal citizens. This was prevalent in, but not limited to the American south where a lot of former slaveholders resided.

These two schools brought about two predominant positions in African Americans, who were the direct victims of the policies and attitudes wrought from these two schools of thought. Some black Americans felt that, regardless of the unfair and unequal treatment that they were meted within America, it was still their home. They were convinced that they had helped to build the country and that they had a stake in it. Thus, their rallying cry was to focus their energies on fighting for social and economic equality, and a seat at the governing table. The other group did not see it this way. While they recognized that they had labored hard for and in the country for so long, they also believed that they would never attain true equality in a country where most of its population and leadership saw them as inferior. This group was determined to go back to Africa, to “Christianize and civilize” the natives, and build a country that could be called a “black superpower.”

They believed that having a black country that had a real stake and voice in world politics would correct all the misconceptions of the western world about Africa and Africans in general. To this end, this group gathered thousands of African Americans and left the shores of the United States to found their nation in Africa. They called it Liberia and declared it a republic in 1847.

Their ideas and actions seem to be the earliest practical application of Pan African thought.

The Conception of Pan Africanism: An Intersection of Struggles.

Pan Africanism appeared at the intersection of these two events and their principal characters. While the incursion of the British sphere of influence came with its attendant woes, it also bore good and useful gifts like western education, among other things. The establishment of a colonial theatre in Freetown as far back as 1808, served as a launchpad for a crop of western-educated Africans, who, in subsequent generations, rejected British cultural influence and instead opted for their traditional African cultural mores and ideology. Towards the tail end of the nineteenth century, it wasn’t strange to find Africans named Davies, Williams, and Vincent to switch back to Faduma (Fadunmo), Sapara, and Agbebi.

In the highly intellectual and anti-colonial circles, at some point, it became a social anathema of sorts for Africans to have ‘westernized names’, as the virulent Pan Africans would liken them to race traitors. For example, Mojola Agbebi, a Yoruba Baptist minister — and ardent Pan Africanist — after his ordination in Liberia in 1894, proclaimed: “I believe every African bearing a foreign name to be like a ship sailing under foreign colours and every African wearing a foreign dress is (emphasis his) like the jackdaw in peacock feathers.” His birth name was David Brown Vincent.

This posture of self-determinism, cultural and political independence underscores the initial aim of what could pass off as Pan Africanism on the part of native Africans who, from what we have gathered so far, form one of the two pillars of Pan Africanism.

Over in the American sphere of influence, which essentially covered the United States, Liberia, and some afro Caribbean nations like Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, and Haiti, the struggle took on a different form. While the Liberians and their dream of “Christianizing and civilizing” Africa were being run into the ground by their ineffectual leadership and poor governance, African Americans in America still pressed on with the same struggle that brought about the need for emigration to Liberia in the first instance — racial inequality.

After about forty years of existence, Liberia’s sphere of influence was still, contrary to plans, quite limited to Liberian space, and they were even having problems with some natives in their own space. Hence, the pipe-dream of “Christianizing and civilizing Africa” was dying a slow, painful death.

Some African Americans still kept the dream alive, however. One of them was Martin. R. Delany, a black, Harvard-trained medical doctor, who, though still living in the United States, was a huge supporter of the emigration of African Americans to Liberia. Delany visited Liberia in 1859, and, instead of staying in there, decided to explore other areas of West Africa that would be suitable for the resettlement of other African Americans. He eventually settled for Abeokuta, in present-day Nigeria, and made a deal with the chiefs there to obtain large swathes of Egba (the collective name for the people in Abeokuta) land in exchange for western education and knowledge of the arts, sciences, agriculture, and other mechanical and industrial operations.

This agreement broke down years later, after the British colonialists launched a propaganda war against the African Americans, alleging that they were rabble-rousers, and would be nothing but trouble for the Egba people. The struggle for racial equality in mainland America and the Caribbean, coupled with the concerted effort to increase African American influence in Africa via Liberia, underscores the version of Pan Africanism that was looming over the American sphere of influence.

This, of course, forms the second of the two pillars of Pan Africanism.

The Birth of Pan Africanism: A locus of Ideas.

When, eventually, the idea of a concerted effort for the amalgamation of the different ideas of what could pass off as Pan Africanism was broached, it was neither by an African born and living in Africa, nor by an African American born and living in America — or Liberia for that matter. Pan Africanism as, first, an Association to be called the African Association, was introduced by two Afro Caribbean men named Henry Sylvester Williams (a Trinidadian lawyer) and Reverend Henry Mason Joseph (a Christian minister in Antigua, British West Indies), among others. However, they were both based in London at the time, which for all intents and purposes is a part of the British sphere of influence in relation to Pan Africanism.

In 1891, Cecil Rhodes’ South Africa Company seized the lands of the natives of the Ndebele nation, in what is now Zimbabwe. Towards the middle of the decade, King Lobengula of Ndebele sent a delegation to London to seek help from Queen Victoria, but they only got an audience from Neville Chamberlain, the Colonial Secretary, who informed them that the Queen’s hands were tied about the matter and that there was very little that he could do. He, however, assured them of his “deepest sovereign sympathy.”

Alarmed by this development, Williams, Joseph, and others, who were in London at the time, and had helped to lobby the colonial government for the case, decided, on 24 September 1894, to found the African Association, “to encourage a feeling of unity and to facilitate the friendly intercourse among Africans in general; to protect the interests of all the subjects claiming African descent, wholly or in part, in British colonies and other places, especially in Africa, by circulating accurate information on all subjects affecting their rights and privileges as subjects of the British empire, by direct appeals to imperial and local governments.”

In a move that finally cemented the two pillars of Pan Africanism as one, Booker. T. Washington, the undisputed, most influential African American thinker of the time and the head of the Tuskegee Institute in Oklahoma, paid a visit to Great Britain in 1899. There, he was able to interface with the heads of the African Association. Admittedly, Washington — like many other African Americans who had never been to Africa, nor been in close contact with a large number of Africans — viewed Africans in an unfavourable light, mainly due to the erroneous information about Africans that he had been exposed to in America. His appearance in London changed all this. In one of his writings about the experience, he remarked that “It is surprising to see the strong intellectual mould which many of these West Africans and West Indians possess.” This meeting invariably opened up the American Pan African sphere of influence to its British counterpart. Ideas and experiences were traded, and a movement emerged off the back of the common struggle of the black man all over the world. If the African American suffered from exploitation, degradation, injustice, and inequality, then his brother across the ocean suffered the same fate, albeit in different measures.

At this time, Pan Africanism’s main goal became, to “protect Africa from the depredations of the empire builders.” Therefore, the ultimate resolution of the Pan African conference of 1900 was to wrest Africa from the colonial powers, and to build a continent that could prove to the world that the black race was entitled to belong to the “great brotherhood of mankind”. While putting the two spheres of influence together to form one movement, the proponents recognized that even though the Africans and African Americans were being oppressed by different nationalities, at home and abroad, their problems were conjoined. It was down to one thing: the black man was not respected, and fixing only one side of the problem would not solve the general problem.

W.E.B. Du Bois’ speech at the American Negro Academy meeting, which came up after the first Pan African conference, in October 1900 captures the importance of the resolution of the conference: “It is but natural for us to consider that our race question is a purely national and local affair, confined to nine million Americans and settled when their rights and opportunities are assured… yet, a glance over the world at the dawn of the new century will convince us that this is but the beginning of the problem — that the colour line belts the world, and that the social problem of the twentieth century is to be the relation of the civilized world to the dark races of mankind. If we start eastward tonight and land on the continent of Africa, we land in the centre of the greater negro problem — of the world problem of the black man.”

A conference that was convened primarily to “influence public opinion” about Africa and its peoples had suddenly donned a militant garb, proclaiming a resolution of total liberty and freedom for Africa. But no surprises there, it is what happens when the downtrodden come together to trade stories and find a common ground. Two bumbling spheres collided in London in 1900 and a cataclysmic explosion occurred — one that is still burning around the world to date. Pan Africanism was born.

Great Read …Looking forward to your next post

It is as good as anticipated. Quite informative….

That’s helpful. Great write-up 🔥

Loved every bit of this!